According to the World Bank Group's Doing Business Rank, China has moved up 15 places from 2018 and 47 places from 2017 respectively. China’s Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) believes that Chinese courts have made a significant contribution to that.

On 24 Oct. 2019, the World Bank Group published its Doing Business Report 2020 (hereinafter referred to as “Report 2020”. Click here for full text), showing that China not only climbed to the 31st place in the World Bank Group's Doing Business Rank, but also joined the ranks of the world's top ten most improved economies for ease of doing business for the second year in a row thanks to a robust reform agenda.

The SPC published 12 articles in a row on its official website to introduce Report 2020 and stated that Chinese courts had made great efforts to improve China's ranking in it, indicating that the SPC takes this report very seriously.

I. What does the Report 2020 say?

According to the official website of the World Bank Group, Report 2020 is its flagship publication, which presents quantitative indicators on business regulations and the protection of property rights that can be compared across 190 economies.

Report 2020 shows that the economies with the most notable improvement are Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Togo, Bahrain, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, China, India, and Nigeria.

Compared with the 46th place in Report 2019, China is at the 31st place in the Ease of Doing Business Ranking in Report 2020, rising 15 places this year.

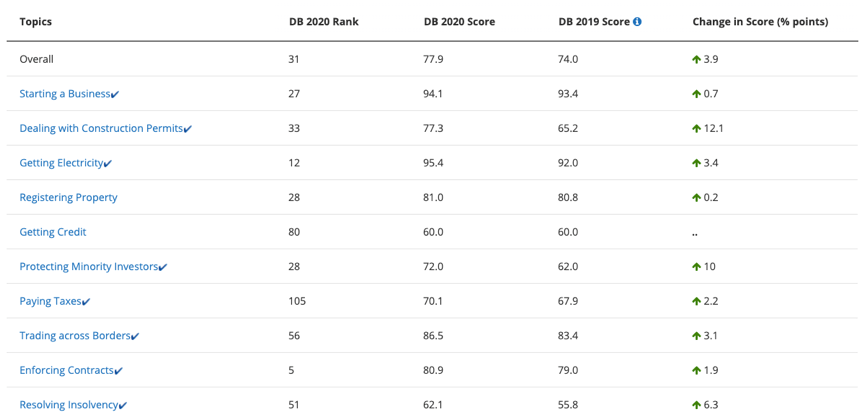

Besides, China's place in each Topics Ranking has also moved up as follows:

(Source: World Bank Group’s Doing Business)

II. Chinese courts' contribution to China's ranking

On 26 Oct. 2019, the SPC's official website reproduced "China's doing business ranking jumps to 31st, indicating that the achievements of judicial reform have been recognized" (中國營商環境排名躍升至31位意味著司法改革成果得到認可), an article first published on the People's Daily (人民日報) App. [1]This article stated that the SPC was responsible for three of the reforms related to the Topics Ranking in Report 2020, namely Enforcing Contracts, Resolving Insolvency, and Protecting Minority Investors.

However, most of the SPC’s other articles seemed to focus more on Enforcing Contracts and Resolving Insolvency, and did not provide much introduction on Protecting Minority Investors.

The article introduced the following reforms that the SPC implemented during the evaluation period of Report 2020, which contribute to improving China’s ranking:

(1) Amend the “Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Strictly Regulating Extension of Trial Period and Postponement of Hearing for Civil and Commercial Cases” (最高人民法院關于嚴格規范民商事案件延長審限和延期開庭問題的規定) to improve the efficiency of trials;

(2) Issue the “Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Disclosure of Judicial Process Information by People’s Courts through the Internet” (最高人民法院關于人民法院通過互聯網公開審判流程信息的規定) to increase judicial transparency;

(3) Issue the "Opinions of the Supreme People's Court on the Coordination of Case-filing, Trial, and Enforcement" (最高人民法院關于人民法院立案、審判與執行工作協調運行的意見), clarifying the division of labor and collaboration within the courts, so as to help the litigants realize their rights and interests through litigation more promptly;

(4) Issue the "Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Enterprise Bankruptcy Law of the People's Republic of China (III) " (最高人民法院關于適用〈中華人民共和國企業破產法〉若干問題的規定(三)), adjusting the bankruptcy procedures in China according to the assessment system of the World Bank's Doing Business Report.

(5) Issue the “Notice on the Separate Assessment of Performance of Compulsory Liquidation and Bankruptcy Cases” (關于強制清算與破產案件單獨績效考核的通知), which stipulates a separate assessment of judges' performance in handling liquidation and bankruptcy cases, thereby encouraging judges to better handle such cases;

(6) Issue the "Provisions on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Company Law of the People's Republic of China (V)" (關于適用<中華人民共和國公司法>若干問題的規定(五)), improving the mechanism for protecting the rights and interests of minority investors; and

(7) Issue the "Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues Concerning the Case Trial by Internet Courts" (最高人民法院關于互聯網法院審理案件若干問題的規定) to reduce the time and cost for litigants.

An article on the SPC's official website stated that the SPC had set up a special working group, which made a list of tasks and a timetable according to the World Bank's assessment criteria, and allocated different tasks to the SPC as well as the courts in Beijing and Shanghai separately. [2] I think this suggests that the World Bank's assessment is indeed pushing Chinese courts to reform.

Another article expressed that the World Bank's evaluation of "Enforcing Contracts" focused on the whole process from case filing and trial, to enforcement and document disclosure, which exactly corresponds to the aim of the SPC's latest round of judicial reform since 2014. [3] Therefore, the article believed that Report 2020 had demonstrated at least a staged success of the SPC's judicial reform.

Interestingly, Mr. Luo Peixin (羅培新), a Chinese expert representative in consultation with World Bank and also the Deputy Director of Shanghai Justice Bureau, said that the provisions promulgated by the SPC to improve the ranking were, in essence, judicial interpretations, which was not recognized by the World Bank at first. For that reason, Mr. Luo had made a special trip to the World Bank to explain the effectiveness of judicial interpretations in China. [4] (For more information on the effectiveness of the SPC's judicial interpretations, please refer to this article)

III. How does Report 2020 describe China's Enforcing Contracts?

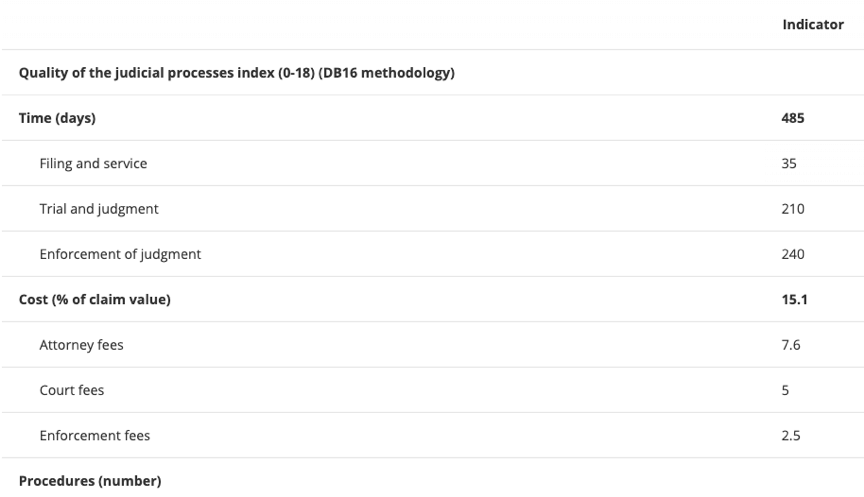

According to this report, in China, it will take the litigant 485 days on average from suing to the enforcement of a judgment, and the costs account for 15.1% of the claim value.

(Source: World Bank Group’s Doing Business, Data)

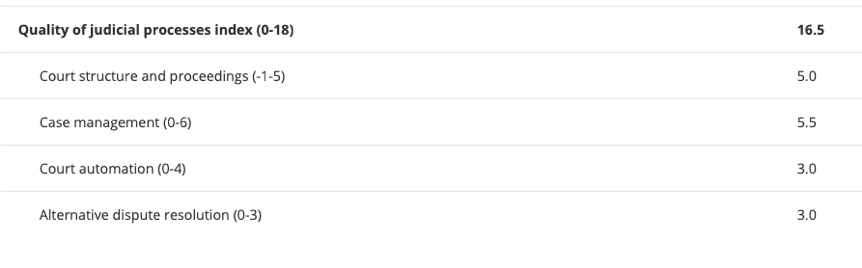

China scores 16.5 points in the Quality of judicial processes index (0-18).

(Source: World Bank Group’s Doing Business, Data)

I compared the indicators of time, cost and quality of judicial processes between China and other countries, mainly including the average level of High-income OECD Economies, the average level of countries in the same region (i.e. East Asia & Pacific Countries), the three major countries near China (i.e. Singapore, Korea, and Japan), as well as the two typical countries of common law (i.e. the US and the UK).

The comprehensive data is as follows:

|

|

Time(Days) |

Cost (% of claim value) |

Quality of judicial processes index (0-18) |

|

China(Shanghai) |

485 |

15.1 |

16.5 |

|

High-income OECD Economies |

589.6 |

21 |

11.7 |

|

East Asia & Pacific Countries |

581.1 |

47.2 |

8.1 |

|

US (New York City) |

370 |

22.9 |

15.0 |

|

UK |

437 |

45.7 |

15.0 |

|

Singapore |

164 |

25.8 |

15.5 |

|

Korea |

290 |

12.7 |

14.5 |

|

Japan |

360 |

23.4 |

7.5 |

In short, Chinese courts may not be the best performer in terms of the timing indicator, but are still above average.

The comparison of time cost for each stage of the proceedings is as follows:

|

|

Filing and service |

Trial and judgment |

Enforcement of judgment |

|

China(Shanghai) |

35 |

210 |

240 |

|

US(New York City) |

30 |

240 |

100 |

|

UK |

30 |

345 |

62 |

|

Singapore |

6 |

118 |

40 |

|

Korea |

20 |

150 |

120 |

|

Japan |

20 |

280 |

60 |

Clearly, in terms of the time of filling and service, the difference among these countries is not substantial; as for the time of trial and judgment, China is at a medium level; but when it comes to the time of enforcement of judgments, China lags far behind other countries. The SPC has long been aware of this problem and has been putting significant efforts to solve it since three years ago. (For more information on China's efforts in enforcement of judgments, please refer to this article)

Comparison of litigation costs:

|

|

Attorney fees |

Court fees |

Enforcement fees |

|

China(Shanghai) |

7.6 |

5 |

2.5 |

|

US(New York City) |

14.4 |

5 |

3.5 |

|

UK |

35 |

9.5 |

1.2 |

|

Singapore |

20.9 |

2.8 |

2.1 |

|

Korea |

9 |

3 |

0.7 |

|

Japan |

18.5 |

4.5 |

0.5 |

It’s interesting to note, although there is little difference among these countries in court fees and enforcement fees, the attorney fees vary widely, and China has the lowest attorney fees. That is probably because, instead of charging an hourly rate, Chinese lawyers generally charge on a flat fee basis plus a contingency fee basis, the latter of which amounts to a certain percentage of the claim value. The advantage of this arrangement is that the parties can estimate their costs in advance. (For more information on China’s lawyer fees, please refer to this article)

It is noteworthy that for the indicator “Can the initial complaint be filed electronically through a dedicated platform within the competent court?”, the World Bank’s evaluation of Chinese courts is “NO”. The SPC was originally proud of its E-Justice innovation, but as an article on its website acknowledged, China’s Internet courts might have not met the World Bank’s requirement. [5]

IV. How does Report 2020 describe China's Resolving Insolvency?

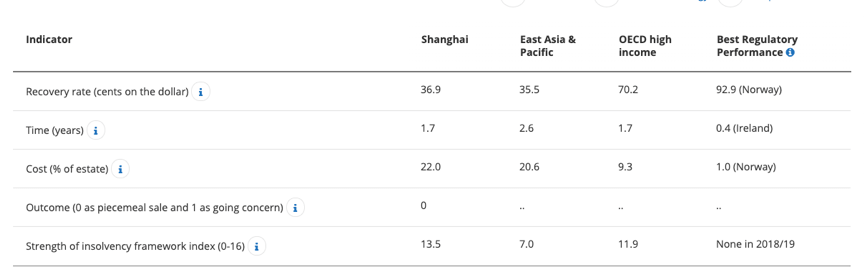

According to this report, in China, the recovery rate of insolvency is 36.9, the time is 1.7 years, and the cost is 22%. This data is much better compared with that in the past. I was a bankruptcy lawyer 10 years ago. At that time, a bankruptcy case would usually last for 4 or 5 years with a recovery rate of around 10%.

Comparison of China with other countries:

|

|

Recovery Rate |

Time(year) |

Cost(%) |

|

China |

36.9 |

1.7 |

22.0 |

|

High-income OECD Economies |

70.2 |

1.7 |

9.3 |

|

East Asia & Pacific Countries |

35.5 |

2.6 |

20.6 |

|

US |

81.0 |

1 |

10.0 |

|

UK |

85.4 |

1.0 |

6.0 |

|

Singapore |

88.7 |

0.8 |

4.0 |

|

Korea |

84.3 |

1.5 |

3.5 |

|

Japan |

91.8 |

0.6 |

4.5 |

As shown above, China has reached the average level of countries in the same region (i.e. East Asia & Pacific Countries), but is below the average of High-income OECD economies. Undoubtedly, China should make more efforts in resolving insolvency. In fact, the SPC has indeed been working hard on this.

The SPC has clearly stated that the "Provisions of the Supreme People's Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of the Enterprise Bankruptcy Law of the People's Republic of China (III)” it promulgated in Mar. 2019 has set up a couple of specific mechanisms in full accordance with the World Bank's assessment criteria. [6]

The SPC also indicated that by the end of 2018, 98 local courts had established liquidation and bankruptcy divisions; in early 2019, Shenzhen, Beijing and Shanghai successively set up bankruptcy courts. Local bankruptcy cases would be heard entirely by their bankruptcy courts in those areas. In addition, as of Sept. 2019, 42 insolvency representative associations had been established in various provinces across the country. [7]These measures have given China a better environment to deal with bankruptcy cases

V. In the future

The SPC expressed in an article that it would continue to take new reform measures to improve its ranking in Doing Business Rank in the future. [8]Nevertheless, Judge He Fan (何帆) of the SPC also said that if any indicator of the World Bank is not consistent with the actual situation in China, Chinese courts would not take action to increase the score of it. [9]

References:

[1] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-194081.html

[2] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-195051.html

[3] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-195071.html

[4] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-194151.html

[5] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-194101.html

[6] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-194081.html

[7] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-194081.html

[8] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-194151.html

[9] http://www.court.gov.cn/zixun-xiangqing-194161.html

Cover Photo by Yiran Ding(https://unsplash.com/@yiranding) on Unsplash

Contributors: Guodong Du 杜國棟